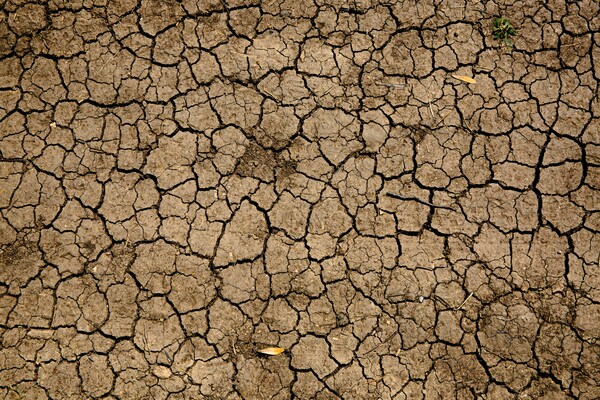

The worst drought in Gangneung, Gangwon-do, occurred in 2025. This drought was considered to be the most severe one since weather observations began in 1911, marking the worst level in 108 years since 1917. Until April, the Obong Reservoir held nearly 90% of its capacity. However, with far less rainfall than usual and a shortened monsoon season, conditions changed dramatically. As the number of heatwave days hits a record high, the reservoir’s storage began to plummet. By June 30th, the water storage level of the Obong Reservoir fell below 40%, reaching the “severe” stage. Gangneung City declared Level 1 activation of the Disaster and Safety Countermeasures Headquarters and gradually tightened the water restrictions. On August 30th, with the reservoir level falling to 15%, the central government declared the nation’s first-ever drought disaster. The Obong Reservoir eventually dropped to a record low of 11.5%.

Water shortage reaches critical levels

Critics argue that Gangneung City’s insufficient response worsened the disaster. The city heavily relies on the Obong Reservoir for 87% of its daily water supply, yet has failed to secure alternative sources. Geographically, Gangneung’s steep terrain makes it difficult for the city to retain rainwater, leaving it structurally vulnerable to water shortages. With limited sites for large dam construction, the need for alternative water sources was clear, yet proactive measures were lacking.

Other neighboring coastal cities also experienced reduced rainfall, but escaped the same degree of water scarcity. This was largely due to drought countermeasures implemented in advance. East Coast rivers flowing from the Taebaek Mountains are relatively short, and the rugged terrain with little flat land limits the construction of large reservoirs. Nevertheless, Sokcho City built an underground dam on the Ssangcheon, which originates in Seoraksan Mountain, and flows into the East Sea, to prepare for drought. Donghae City expanded its water supply with riverbank filtration facilities and reduced water loss by approximately 10% by repairing old pipelines. Other regions managed the drought by utilizing small reservoirs and tapping groundwater. While Gangneung City has plans to construct an underground dam, its delayed response compared to nearby cities is blamed for worsening the crisis.

Damage to crops and communities

The drought inflicted severe damage on the agricultural sector. Gangneung City reported that between September 9th and 19th, 275 farm households filed crop damage reports, and the number is expected to increase further. Heat and water shortages ruined field crops on many farms, particularly affecting highland cabbage and radish. Farmers in Gangneung’s mountainous regions, who depend on small reservoirs and groundwater, faced the most severe challenges as their water sources dried up completely. Some farmers resorted to purchasing water at high prices or transporting it from neighboring cities just to save a portion of their crops. Local agricultural cooperatives warned that the prolonged drought could cause long term price instability for key produce. Although heavy rains in mid-August restored the Obong Reservoir’s water level to 60% and led to the lifting of the disaster declaration, it was too late to revive the crops that had already withered.

The drought significantly disrupted daily life for many residents, exacerbating the severity of the crisis. Water use restrictions affected 123 large users with storage tanks over 100 tons and 45,000 households. However, during supply hours, residents reported muddy and or bluish water coming from their taps. Residents voiced frustration, stressing that ensuring a reliable water supply was their top concern. In response, the city distributed bottled water, securing 8.73 million two liter bottles for distribution to residents. Volunteers assisted elderly and low income households with water delivery.

Emergency water release and waterworks renovation are effective solutions

As the Obong Reservoir level dropped into the 10% range, authorities resumed operations at Pyeongchang’s Doam Dam, which had been closed for 24 years due to environmental concerns. Emergency releases of 10,000 tons of water per day were carried out to supply the Hongje Water Purification Plant in Gangneung. The city also shut down public swimming pools and adjusted water pressure in public restrooms as part of its emergency measures.

Nevertheless, efforts to overcome the challenge continue. On September 26th, Gangneung announced it had been selected for the Ministry of Environment’s subsidized “Aging Waterworks Renovation Project.” The total project cost amounts to 38.4 billion won, of which 21.1 billion won comes from national and provincial funds, and 17.3 billion won is provided by the city. From 2026 to 2031, 37.4 km of aging pipelines in the Dosan dong, Noam-dong, and Ponam-dong districts will be replaced. The city aims to increase its water utilization rate to 85%, reduce leakage-related waste, and enhance water quality stability, ultimately preparing for extreme droughts while reducing long-term maintenance costs.

The Gangneung drought was not merely the result of climate change, but a complex disaster shaped by regional vulnerabilities and administrative shortcomings. The cases of neighboring cities that minimized damage through proactive measures clearly show the path Gangneung must take. Gangneung must use this crisis as an opportunity to restructure its water management and adopt long-term measures to address future climate challenges. Nationwide bottled water distribution and the suspension of school meals revealed how severely the city was unprepared for the drought. Some residents even had to travel to other regions just to wash dishes. These scenes should never be repeated. As climate change accelerates, water scarcity will no longer be an exception but a recurring threat. Gangneung’s failure to act swiftly and strategically turned a foreseeable risk into a preventable disaster. What matters now is whether the city can turn this lesson into lasting reform by strengthening infrastructure, diversifying water sources, and preventing administrative complacency from endangering its citizens again.